Jonathan Waters

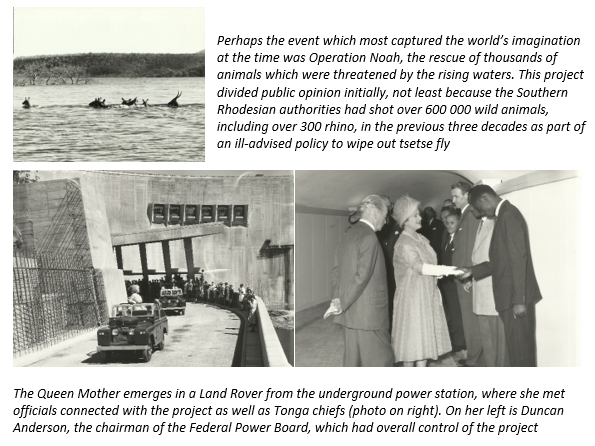

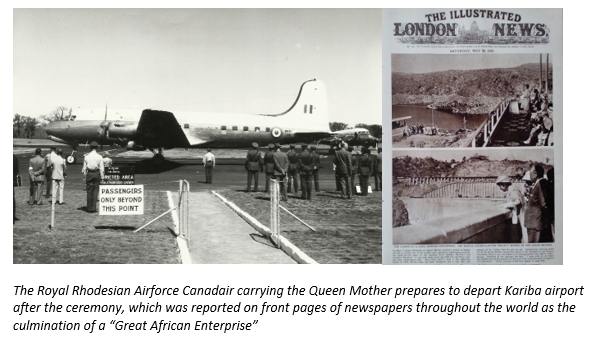

SUNDAY May 17 marks the 60th anniversary since Kariba Dam was officially opened by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother. At 10:57am on what was a Tuesday morning, the Queen Mother pushed a button to start the second generator of what had been designed to be a single purpose power project, which saw the additional creation of fishing and tourism industries in the decades that followed.

Kariba was the showpiece of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, which in reflection, was already in decline when the Queen Mother arrived on May 11. But it was to be a triumphant three week visit in which she was to extensively tour all three territories, starting with the opening of the first Central African Trade Fair, still running today as ZITF.

The project to build what remains the world’s biggest manmade dam by volume was a bold measure to deal with the power deficit at the time and was to produce the world’s cheapest electricity. Indeed, Zambia and Zimbabwe are still benefitting from the landmark decision to proceed with this project on March 1, 1955 as power is still generated at less than 3 US cents per kilowatt hour. At the time, the £28m lent to the £80m project by the International Bank was the biggest single loan ever made by what we now know as the World Bank.

The main civils contract was awarded in July 1956 to Impresit, an Italian consortium, who bid £2m less than their closest rival. The Federal government came in for much criticism at the time from British interests for the contract having been awarded to a non-Commonwealth body, but Federal Prime Minister Godfrey Huggins, the architect of the Kariba scheme, pointed out that as most of the money came from the World Bank, it was not funded by British capital.

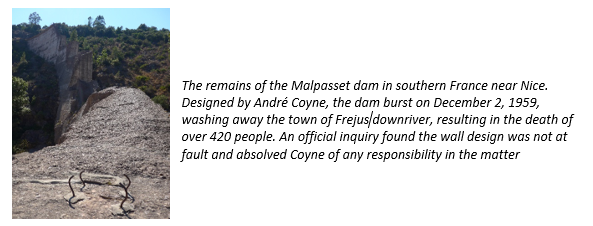

Over the next four years, and despite the works being flooded twice in March 1957 and February 1958 by unprecedented floods, the project was completed on time and £2m under budget. The Zambezi was dammed on December 2, 1958 and Federal Prime Minister Roy Welensky poured the final skip of concrete into the wall on June 22, 1959. The first generator sent power to the Copperbelt three days ahead of schedule on December 28, 1959.

10:57am, Tuesday May 17, 1960 – the Queen Mother officially commissions the Kariba scheme. Behind her is Lord Dalhousie, the Governor General of the Federation of Rhodesia & Nyasaland

Kariba is best explained in terms of numbers as this gives an indication of the sheer magnitude of the project. In simple terms, Kariba contains 180km³ of water, of which 65km³ is the “live capacity” that can be used for power generation. On average, Kariba receives around 45km³ of water every season, mostly (82% of the long-term average) from the catchment area above Victoria Falls.

So when we hear Kariba is “almost empty”, that means it has little water for generating power, but the dam is, at 115km³, still more than two thirds full. At its maximum retention level, the water body stands at 488.5m above sea level while the minimum operating level is 475.5m. That means the “swing” in the water levels for power generation, from “full” to “empty” is 13 metres. The dam reached its all-time low of 475.91m on December 18, 1992.

From the damming of the river in December 1958, Kariba took nearly five years to full to capacity, rising 60m on the wall in the first year alone as the deepest part of the lake was covered. In September 1963, the lake experienced its worst tremors as the placing of 180 billion tonnes of water on the earth’s surface triggered a swarm of seismic events that measured over 6 on the Richer scale and were felt was far as Blantyre and Francistown.

Let me move to the creation of the fishing and tourism industries. Plans for the introduction of species that would be suited to the open waters of a lake as opposed to the river had been made in the 1950s, but the attempts in 1959 and 1962 both failed. The Zambian government persisted in 1967 with trying to introduce a variety of the Tanzanian sardine, which we know as kapenta, but early fishing trials by subsistence methods were a failure.

In 1969, the first kapenta were discovered in the bellies of tigerfish and within a year – according to an inspection of the catch at the annual tigerfishing tournament – comprised nearly 70% of their diet. The Rhodesians conducted trials to see if kapenta could be commercially exploited and a licence was granted to I&J in 1973. The catch rose exponentially in the first few years and private operators were granted licences from 1976 onwards.

Due to the war, the lake had been closed to Zambians for much of the 1970s and on independence in Zimbabwe, the kapenta industry in the north opened up, with many riding on the basic design of the kapenta rig pioneered by Rob Beaton, which remains little changed today. The biomass in Kariba is supposed to support a sustainable annual catch of 50 000t of kapenta but weak policing has seen the official catch fall dramatically from the high point of 27 000t at the end of the 1990s.

The first pioneers in tourism on both sides of the dam were private operators, who provided mainly the curious with the chance to see the new lake. The airlink into Kariba airport sustained the flow of tourists to Zimbabwe’s eastern basin, while Siavonga is less than 200km from Lusaka. The closing of the Mozambique border in 1975 provided a boon for Rhodesian tourism, which gained further traction in the 1980s and 1990s with the building of new boutique lodges and the eponymous “houseboat”.

Quite how Kariba manages to attract so many negative comments about the state of the wall is beyond me. Report after report has declared the wall to be in excellent condition. While there is the expectation that the wall may have moved downstream as a result of water pressure, alkali aggregate reaction in the concrete has resulted in the double curvature arch wall expanding 50mm upstream since 1962. It is also 80mm higher. The threat of the wall breach fed into the Plunge Pool Rehabilitation Project, which in the view of most seasoned engineers, is an utter waste of money.

At this juncture, I would also like to deal with the three greatest Kariba myths, which regardless of me trying to debunk them, will continued to be repeated. Firstly, there are no bodies buried in the wall as the skips could only hold 12 cubic yards of concrete, which in a level pouring would probably cover someone up to their knees. Secondly, it is not the last dam designed by André Coyne that is still standing. Lastly, in the unlikely event that the wall would burst, a tidal wave would not go the whole way to Perth simply because of the inconvenient fact that Madagascar is in the way.

While electricity is the underlying reason for the dam, Kariba’s use has been multiple, varied, and ever changing. We can expect more of this in the next 60 years. Tourism in Africa has seen a shift towards the high end, and upmarket luxury boats on the lake are offering this experience to a wealthy foreigner. The houseboat, coveted by many in the past and the epitome of excess in the 1990s, has lost its lure and is now regarded as an expensive cost centre.

In Zimbabwe there is much navel gazing that things are way off their peak at Kariba, but Zambia has a relatively healthy flow of domestic tourists to Siavonga. The magic of the “Kariba experience” certainly needs to be recaptured for the domestic tourist in Zimbabwe and that will only come when some form of “waterfront development” takes place. As for kapenta, it has become a much more informal business and the ecology of the lake on both sides is threatened by illegal netting and a lack of will to police it properly.

So here we are at the 60th anniversary of our great dam. And it is great as it is still the biggest by volume at 180km³ ahead of Bratsk (169 km³) in Russia. By comparison, Cahora Bassa is only 55km³, less than a third of the volume, although it looks as big on the map. Batoka, if its 196m high wall (versus 128m at Kariba) ever gets built, will hold a mere 2km³. In terms of area covered, the Akosombo dam in Ghana, also built by Impresit, is the world’s biggest at 8 500km² (5 580 km² for Kariba).

On its diamond jubilee, lets raise a glass to the legacy of Kariba. To both Zambia and Zimbabwe, Kariba is more than just a dam. It is part of our psyche. Neither country can think of life without it and for many millions of tourists over the years it has produced many happy memories. The fishing industry has provided thousands of tonnes of protein to the populations of both countries and sustained the livelihoods of thousands. These are two significant fillips of this visionary single purpose project, which in the early years, provided cheap power for industry and agriculture.

Greatly saddened to see no mention of the Batonga. That is an ugly omission in this article and that smells of post-colonialism.

Until 1958, the Batonga were alluvial riverbank dwellers and fishermen, living with the cycle of the Zambezi flooding its banks, tending their ‘river gardens’ yielding two harvests a year, and keeping livestock. They always were quite an anarchistic people, not centrally organised and without a paramount chief. Then the damming of the river at Kariba Gorge for hydro-electric power changed their ways for ever as the water rose and they were forced to move to higher ground. Loaded onto trucks at gunpoint by the British (only approx 37 were shot and killed…), they were dumped many miles away, often in areas with poor soil and without year-round water, given some seed and basically told to get on with it. Their ancestral grounds drowned, scattered over a wide area, they became a forgotten people who understandably lapsed into a kind of dazed apathy, physically separated by Lake Kariba and later on split up into two nations, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The Tonga psyche has a great big hole in it; it can’t be easy for younger Batonga to even find a positive own cultural identity – let alone embrace it. And to top it all, the irony is that their areas were the last to get electricity. To this day, the Batonga still refer to ‘the river’ and never to ‘the lake’.

Hi. There are whole chapters in the book, dedicated to the Batonga. This was just a preview to the book