HARARE (FinX) – For years, Zimbabwe’s reserve position has been the country’s quiet macro weakness. Not because the economy never generated foreign currency, it did. The problem was always the same: the country could not consistently keep it. When reserves are thin, every shock becomes a crisis, every rumour becomes a run, and every policy mistake becomes expensive. That is why the most meaningful signal in the current stability conversation is not the daily exchange rate print. It is the slow, difficult work of building foreign currency buffers and translating them into credible import cover.

The long memory: why reserves became a national vulnerability

Historically, Zimbabwe’s reserve stock has been small relative to its needs. World Bank series for “total reserves (including gold)” shows that Zimbabwe’s reserves have typically sat in the hundreds of millions over long periods, not in the multiple billions that normalise currency and trade stability. A long-run compilation of the same World Bank series highlights how low the base has been: Zimbabwe averaged roughly US$0.32 billion across 1966–2024, with very weak lows in the recent era.

Import cover tells the same story in a more brutal way. Using the World Bank “total reserves in months of imports” measure (a simple “how long could you pay for imports if inflows stopped”), Zimbabwe was reported at roughly 0.13 months in 2023, which is not a buffer, it is a spark near dry grass.

This is why the traditional benchmark matters. The IMF’s work on reserve adequacy consistently points to around three months of import cover as a broadly appropriate rule-of-thumb in many cases, especially for countries seeking resilience against external shocks. Zimbabwe has lived most of its modern economic life below that line.

The 2024–2025 pivot: reserves stop being an afterthought

What changed in the recent cycle is not only rhetoric. It is the data cadence, the stated policy priorities, and the measurable reserve accumulation. The RBZ’s Q4 2025 Quarterly Snapshot explicitly frames stability around disciplined money supply management, exchange rate flexibility under the willing-buyer willing-seller framework, and “consistent accumulation of foreign reserves” as part of the backbone of the local currency regime.

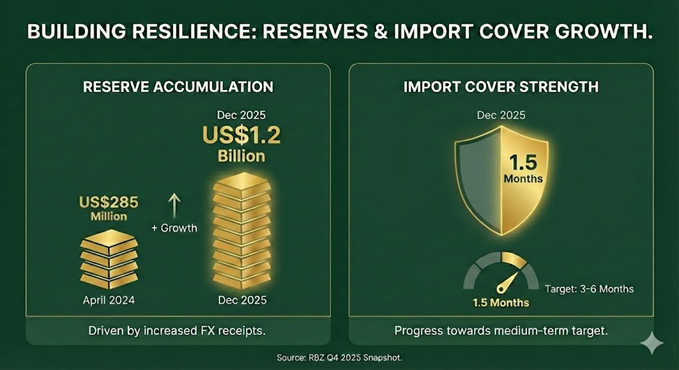

Most importantly, the numbers show a step-up in reserves by end-2025. The Snapshot reports foreign currency reserves at US$1.2 billion, equivalent to 1.5 months of import cover as at 31 December 2025. That single line matters because it signals movement from “no buffer” toward “building a buffer”. It is not yet where the country needs to be, but it is directionally different from the reserve scarcity that defined the prior years.

The same document strengthens the “quality” of the reserve story by showing composition and momentum: cash and nostro balances rising to US$574 million by December 2025, and gold holdings at 4,030 kgs valued at US$566 million. In plain language: this is not just accounting smoke. There is visible accumulation across liquid balances and gold.

The real engine: receipts, surpluses, and the ability to keep forex

Reserves do not grow on speeches. They grow on sustained net inflows, and on the institutional willingness to avoid converting every inflow into immediate consumption, arbitrage, or quasi-fiscal leakage.

On the inflow side, the Snapshot reports total foreign currency receipts of US$16.2 billion in 2025, up from US$13.3 billion in 2024, a 21.8% increase. It also details the structure: export earnings dominated at 59.7%, followed by loan proceeds at 14.8%, and diaspora remittances at 13.5%.

On the “keeping it” side, the same report states foreign currency receipts averaged US$1.3 billion per month in 2025, while external payment obligations averaged US$951.31 million per month, leaving a surplus that averaged around US$400 million. That surplus is the oxygen of reserves. If it is real, sustained, and not recycled into parallel-market speculation, it becomes the raw material for a credible buffer.

It is also consistent with the report’s expectation of a strong external position: a projected current account surplus of over US$1.0 billion in 2025, a jump from US$501 million the prior year.

Import cover: progress, but the gap remains the headline risk

Here is the uncomfortable truth: 1.5 months of import cover is progress, but it is not yet safety. Zimbabwe’s own medium-term roadmap language recognises the target: the NDS2 “conditions precedent” include 3–6 months of import cover. (From the same Snapshot text section on conditions precedent.)

So the honest framing is this: the country has moved from “reserve fragility” to “reserve construction”. But the job is incomplete, and markets will test incompleteness. This is why credibility is built less by celebrating US$1.2 billion, and more by showing how US$1.2 billion becomes US$2.0 billion, then US$3.0 billion, without policy backsliding.

Why this matters for the local currency narrative

Reserve accumulation is not a vanity metric. It is the backbone of monetary credibility. The Snapshot explicitly states that reserves backing the local currency are “around 6 times cover of reserve money” and almost double local currency deposits. This is the kind of ratio that changes behaviour: it reduces the incentive to pre-price depreciation into everything, it weakens parallel market psychology, and it makes “wait and see” possible for business planning.

But there is a trap here: reserve numbers can become propaganda if not paired with transparent rules on how reserves are used, how intervention is conducted, and how money supply is managed. The Snapshot notes RBZ foreign exchange interventions of US$1.34 billion since April 2024 to support market functioning. Intervention can stabilise, but it must not become a permanent substitute for market confidence. The market’s question is simple: are reserves rising despite intervention, or only rising because of temporary inflow luck?

Lat word: A measurable step forward, and a test of endurance

Zimbabwe’s reserve and import cover position is no longer stuck in the “near-zero” zone that made every quarter a gamble. The shift to US$1.2 billion and 1.5 months import cover by end-2025 is a measurable improvement, supported by stronger receipts and a reported external surplus.

Yet the strategic target remains ahead: a credible mono-currency roadmap cannot be built on 1.5 months. The IMF’s “three months” rule-of-thumb exists for a reason: buffers prevent small shocks from becoming regime-ending events.

So the story to watch in 2026 is not whether Zimbabwe can claim stability. It is whether Zimbabwe can compound stability: keep building reserves, push import cover toward 3 months, and prove that the current discipline is not a campaign phase, but a new operating system.